Welcome to Trinity Laban Crosscurrent, a music and dance podcast brought to you by London’s Creative Conservatoire that unearths fascinating and divergent stories in the performing arts.

I’m your host, Will Howarth.

It’s Black History Month and I’ve been learning about the forgotten black musicians of classical music with PhD candidate Uchenna Ngwe, as well as catching up with alumnus Aaron Chaplin of Phoenix Dance Theatre. I’ll be introducing you to Aaron and Uchenna as well as taking you on a Black History walk around Greenwich.

Welcome to the podcast…

Black History Walk with author and historian S.I Martin

[Ambient sounds of the bustling streets of greenwich can be heard]

WH: Passing the market and the Cutty Sark replica I walk towards King Charles Court through The Old Royal Naval College wondering what hidden histories surround me.

We convene for a Black History Walk with historian and author S.I Martin.

SM: I’m Steve, Steve Martin, we’re going to meet a lot of people who I describe as those who fell through the sieve of history. These are the people I find more interesting, ordinary people with ordinary lives, yet who did amazing things simply by surviving.

I’m a big believer in starting where we are. This set of buildings is the site of the Old Royal Naval Hospital. In the 18th century, this country is continuously at war with France and or Spain. So what you saw throughout the 18th century into the middle of the 19th is a huge reliance on black man power by the Royal Navy. Inevitably, many of them were injured and ended up in the buildings around us to be treated. By 1875, 2340 West Indians had been treated here and 599 Africans. A lot of these black sailors actually ended up settling in this part of Kentish London.

—

[Skype Sound]

Interview with BA (Hons) Contemporary Dance alum Aaron Chaplin

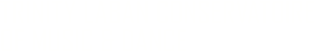

AC: My name is Aaron Chaplin and I studied at Trinity Laban on the BA (Hons) Contemporary Dance course between 2014 and 17.

Image: Aaron Chaplin by Jack Thompson.

WH: Tell us where you’re calling from right now.

AC: I’m calling from Leeds, I’m currently in the Phoenix Dance Theatre part of the Northern Ballet building.

Phoenix Dance Theatre is a medium-scale contemporary dance company, it was founded by three young black boys, David Hamilton, Donald Edwards and Vilmore James in 1981. They had this kind of grit and determination which is still present in the work today, but we’ve evolved, we’re a bigger company now, we’re surviving in this contemporary landscape, it’s become the longest standing contemporary dance company outside of London.

WH: And how did you first become involved with the company?

AC: After my third year at Trinity Laban I applied for Verve and the accompanying apprenticeship schemes and got on to become an apprentice with Phoenix Dance Theatre. I had to travel to Leeds every other week from January until March, it was quite a gruelling process.

WH: Aaron what are you currently working on?

AC: Currently we’re working on our Autumn tour, which is a double bill. We’ve got a version of ‘Rite of Spring’, which was created this year in collaboration with Opera North by Jeanguy Saintus. We worked with a live orchestra and we are also dancing a work called ‘Left Unseen’ by a choreographer called Amaury Lebrun.

Both those works are very different, ‘Rite of Spring’ visits the ideas of Haitian folklore and the characters that are present within that, the Voodoo culture, the rituals and the idea of offerings. While ‘Left Unseen’ is the exploration of how we navigate with the five senses and the ideas of inclusivity, exclusion, and isolation.

That’s what we’re currently working on, and then later in the year we have a new creation called ‘Black Waters’ which premieres in February of 2020, which touches upon the Zong massacre, which happened in the Caribbean. Essentially there were slaves taken from Africa and they were brought over to the Caribbean, they docked in black waters in Jamaica, but on the way there before they docked they’d run out of drinkable water so they threw some of the slaves overboard with the hopes of docking and claiming the compensation on their lives.

WH: It sounds as if Phoenix Dance Theatre is doing the important work of telling the stories that make us feel uncomfortable.

AC: Mm, I think it’s really important. Creating work that actually starts a conversation, that really resonates with you and changes the way you think about things. I think these past few productions, Phoenix has really brought that to the table.

WH: I wanted to talk about a production that the company did last year, in 2018, which was called ‘Windrush: Movement of the People’.

AC: ‘Windrush: Movement of the People’ was premiered in February of 2018. To explore the narrative of the empire Windrush, that arrived from the Caribbean to the UK. There were 492 people on that ship, they all had their own stories.

WH: So perhaps you could tell us a bit more about how you were involved with the creative process?

AC: Yeah absolutely. It was choreographed by Sharon Watson but we had a lot of influence into it, in terms of the movement and where we took the emotions of the piece. Sharon gave us the structure and informed us, but we were allowed our own red thread through it. There was just a lot of smiling and laughter because we were taking this Caribbean flavour and having fun with it. We were trying out new things, I mean there were people in the company who had never moved in that way before, and there were people in the company who had, so it was a kind of a blending of the contemporary dance culture and the Caribbean dance culture.

The piece was split up into two sections, you had the beginning section where we were in Jamaica, which was very flavourful, very light hearted. And then you had a second section which we referred to as ‘you called and we came’; we arrive in this smoky, dimly lit stage, we have jackets on and it feels like our spirits have been trampled, it feels like we’ve arrived in somewhere where we don’t belong.

I remember speaking to my nana, who came over in 1965. Having been told that the streets were paved with gold, there was an expectation that wasn’t met, and to be faced with such racism and such hatred when they’d only come to answer the call, they had to re-evaluate their own feelings towards the country.

—

[Music Interlude]

WH: If you leave King Charles Court from the north gate facing the river and walk left, just past the old brewery is the visitor centre for the Old Royal Naval College. If you enter through the revolving door and look behind you, you will see a small inconspicuous plaque.

SM: Isn’t it discreet? [laughing] Amongst my other sins, I also work with English Heritage on their blue plaque’s, and one of the things for us that’s been flagged up is the very low profile of black people of African origin.

But, it’s here to commemorate the presence of a gentleman by the name of John Blanke, who was described as the black trumpeter to the King’s Henry VII and VIII, so he is the first sign of black presence here. The leading theory is that he arrived with the numbers of black ‘amors’ as the term was, who arrived with Catherine of Aragon in 1501. The Iberian peninsula having had a longer connection with the African Continent.

—

[Music Interlude]

Interview with Trinity Laban PhD Candidate Uchenna Ngwe

UN: My name is Uchenna Ngwe, I’m an RDP Creative Practice student. The title of my thesis is ‘Beyond Coleridge-Taylor: presenting classical performance and the legacies of musicians of African descent prior to 1970.’

WH: What first sparked your interest in this topic?

UN: When I was trying to put together a programme for my chamber ensemble, the Decus Ensemble, I was looking pieces that would go with Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Nonet. I thought it was quite interesting looking at his heritage, to find out pieces by other composers of African descent. So I started looking around that, looking at what other people were doing, and I realised that although there are a lot of classical composers and musicians around historically, there isn’t really much written about them and most of their pieces actually don’t get performed very often, so I wanted to look at ways of promoting their work.

WH: Who were they key black composers and musicians?

UN: There were quite a few. George Bridgetower, most people know as a violinist who worked with Beethoven at one point until they had a falling out, as Beethoven tended to do with people [laughing]. He also had at least one brother, they think possibly two, but there was a brother Frederick who was a cellist and who was also a composer.

As well as them, there was Joseph Emidy, a formerly enslaved violinist who was born in Africa and ended up in Portugal playing in the Opera House in Lisbon. Then was press-ganged onto a ship and dumped in Cornwall, so quite an interesting life Joseph Emidy had, but he had a number of sons who all ended up becoming professional musicians. One of those, Thomas Hutchins Emidy published a few pieces, mostly working with brass bands but also a few piano pieces, and one of those exists at the British Library.

WH: You’ve said that there isn’t really a lot of musicological work that’s been done on these composers, what are the sources that you go to, to find out about them?

UN: My focus has been on how this music has been presented in the UK, so there is a lot of going through historical newspapers and letters and things like that you can find quite easily at The British Library. Newspapers have been the best way for me to access information about what people were really thinking at the time.

WH: Many of the people that you’ve mentioned so far have lived in Europe, I’d be interested to know whether the world’s of native music in Africa or in the Caribbean and the colonial music brought from Europe, were separate, or if there was much dialogue between them?

UN: Before the 2oth century there wasn’t, and classical music actually was used as a force for colonialism. In the late 19th and early 20th century music college were being established and lots of church musicians from African and English speaking colonies were coming over to study music and then go back home and establish music education in the European form. Then, there was starting to be this idea that traditional forms of music, which had previously been banned, were allowed in hybrid forms, and that’s when you had people like Samuel Akpabot of Fela Sowande in the early to mid 20th century looking at ways of sort of combining the two.

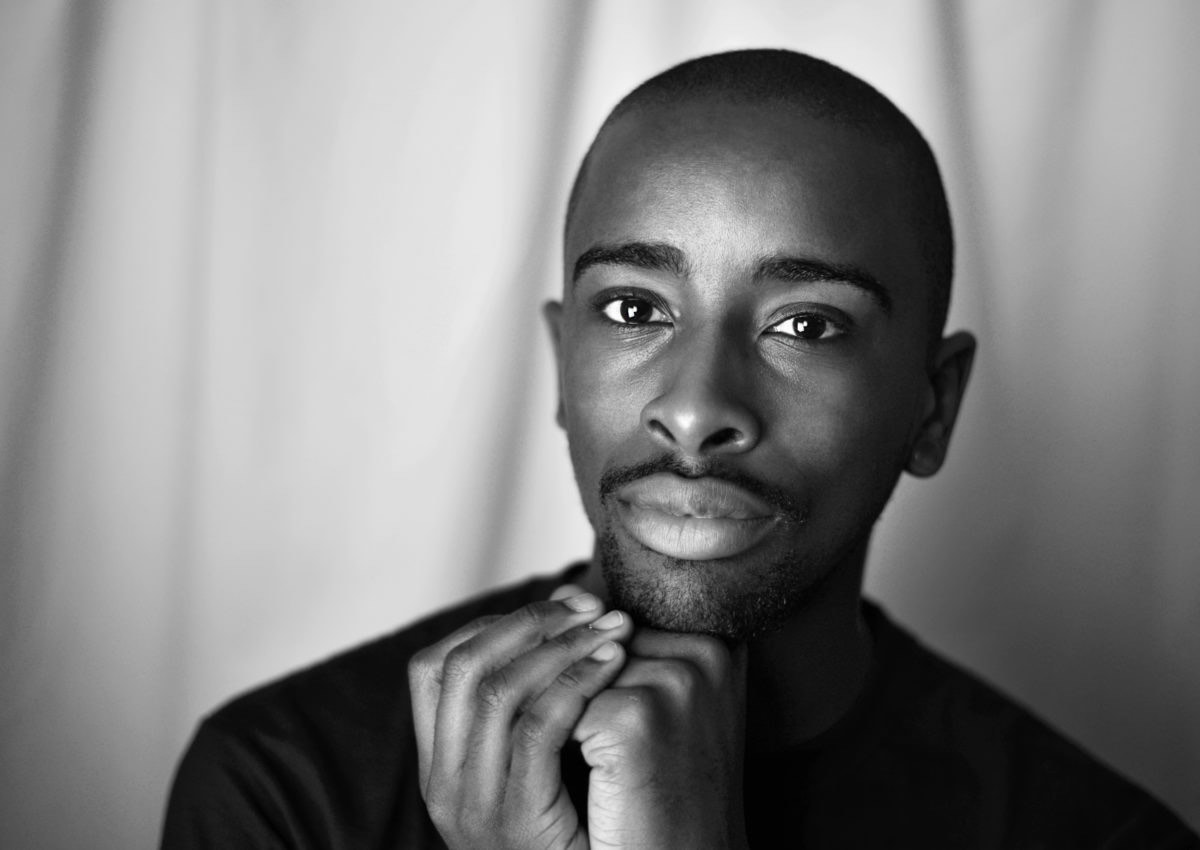

WH: You mentioned Fela Sowande, could you tell us a bit more about who he was?

UN: Yes, he was a Nigerian composer, pianist, organist, ethno-musicologist and he came over here to study in the 30s. His career was extremely varied, he initially became popular playing Jazz because it was around the time of the birth of British Jazz. There are lots of records at the BBC which show the different programmes he played on. So he would play the organ for 10 minutes on one show, then he would accompany Gracie Fields doing some songs and then he would be with a jazz band doing something else. After living here for a few years he then went over to the states and ended up running an ethno-musicology department, and it’s quite early in the days of ethno-musicology.

Image: Fela Sowande

WH: Could you suggest one or two of his compositions that we ought to add to our listening lists?

UN: My favourite one, probably the one that’s easiest for people to get, would be ‘The African Suite for Strings’. That’s a really, really lovely piece and I believe that was used on Canadian broadcasting as their theme tune for quite a while.

—

[Music Interlude]

WH: Breathlessly reaching the top of the hill by the Observatory, we look out across the expanse of the park and Canary Wharf beyond [sounds of nature]. Stripping away the modern architecture and skyscrapers, we imagine how it might have looked in centuries past.

SM: Wasn’t it worth it for the view?

Here we are in Greenwich park looking from here is Christopher Wren’s eye-view, through the Queen’s House, through the old seaman’s hospital, into the Thames. It always strikes me when I look at that stretch of water, that over 3000 slaving voyages took place from docks on the banks of the Thames. It strikes me doubly because when you ask most Londoners to name a city in these Islands associated with the trade in human lives across the Atlantic, most of us are going to say Liverpool, Bristol, and it’s forgotten that this is where it started. And, even though Bristol had 5000+ voyages London has the ugly second place.

—

[Music Interlude]

[Skype Sound]

WH: Aaron Chaplin, What does Black History Month mean to you?

AC: For me Black History Month is a celebration of black excellence. I think there needs to be an understanding that we are only standing on the shoulders of giants. So we need to acknowledge those who came before us because those are the people who have enabled us to live the life that we are living now.

And, when I say black excellence I don’t just mean everyone whose recognised and adored in the public sphere, it’s also the people who are the backbones of the community, people like my grandmother who left two kids in the Caribbean, started a new life here in the hope of inviting those children over and paying into the National Insurance and doing her bit. Those are the people who aren’t necessarily recognised, I think we take the time to be taught about the Martin Luther King’s and the Rosa Park’s and the Samuel Beaver’s of the world, who did great things, but they could only do those things because the people who they arrived with, or were of the same hue as them, were also putting in the work to further their people, to help the generations to come.

I think it’s important to celebrate black people who have done something to change the world, but the people who we live with, our grandmothers, our mothers, our fathers, our uncles, our brothers, they change the world every day. I think for me Black History Month is an acknowledgement that I should be doing this every day of every year.

WH: There is a really clear message emerging from what you’re saying which is that Black History Month is not only looking at things that have happened but also helping people to believe that they can continue to make black history.

AC: Absolutely. In this internet age where everything is tangible, nothing is out of your reach. We’ve seen people do their own thing and become successful out of it and I think this is a time where we can really harness black talent, nurture them and bring them to the forefront.

WH: What do you think we could be doing more of to help that to happen?

AC: There is an elitist idea of the arts I think, and it it’s been passed down from generation to generation. This kind of, you must achieve the academic to be successful, and the arts are kind of frivolous. I was told by teachers that you’re never going to make money off dance, you’re never going to be rich and successful being a dancer, and I think we need to not spew that rhetoric, we need to push the idea of success in dance to young people of colour. You can create your own streams of income being creative.

WH: Historically, black people making art have not really been recognised and so there’s a certain attitude which is if we’re not to be recognised then why would we bother making anything. But then of course this just perpetuates the problem.

AC: Yeah exactly that, if young black creatives don’t take the step to create work and put our imprint in the arts space then in 20 years, 40 years, when the V&A wants to do a new exhibition about dance, will we see ourselves represented?

—

[Music Interlude]

WH: Coming to the riverside we look west, upstream to the former docks at Deptford.

SM: Deptford was where, in 1786, three vessels were moored for the reception of 349 members of London’s black poor community. As the period description says, they were becoming to intrude on the observation of the great and the good, being unsightly. The solution to their presence was to simply shift them all on mass to Sierra Leone. And this is exactly what happened. In 1787 the gentleman who was giving the job as provisioner or commissary for that expedition was Olaudah Equiano. He is generally accepted as being the first black, high-profile civil-rights leader. His presence here in 1786 was his second visit to Deptford. He has been down that river as a young man: in 1759 he had actually been on board a British warship which had just come up from Plymouth. Truthfully he was an enslaved servant to a Lieutenant, Lucas. Equiano, being someone who was very high-spirited and autonomous thought himself free and he was very surprised to find himself being lowered over the side of the boat into a waiting barge which his master ordered to be rowed down the Thames, so he was actually sold on to the owner of the vessel The Charming Sally in Gravesend. He was fourteen years old at the time. Little did he know that he’d return to the that same point in the river in Deptford where he’d become the first Black civil servant.

—

[Music interlude]

WH: And now to our guest, PhD candidate Uchenna Ngwe.

WH: Many of us may have heard of Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, who is often called ‘The Black Mozart’

UN: Yes, he was the son of an enslaved woman from Guadeloupe, and his father was her slave owner. They moved together to Paris when he was quite young, which is where he was renowned for his life in the military, but he actually also was a really well-known violinist playing in the Paris Opera and he was made a Chevalier – the equivalent of a knight – which meant that when he came over to London at various points there were only specific places that he could perform in due to his status. He couldn’t perform publicly so he actually performed in private clubs.

Image: Saint-Georges by Mather Brown, 1787

WH: So the stipulations about where he could and couldn’t play were based on his military status rather than the colour of his skin?

UN: Exactly, the difficulties that he did find were in romantic relationships that he had. Because his father was a white man who was quite high-up in social status it meant that he spent most of his time around people of a certain class but he actually couldn’t marry them because of his colour.

WH: The nickname he’s often given, ‘The Black Mozart’, I wondered whether you think it’s a justified nickname?

UN: The more I have found out about him the less I think it’s justified! [laughing] He doesn’t really have much to do with him musically, and their lives were obviously very different as well. It’s been quite interesting finding the links between them. They were in Paris at the same time and, in fact, I have found once source that says he lived in the same house as Mozart’s mum at one point, so they probably did know each other. But musically, and stylistically, they’re very different.

WH: My feeling is that to call him ‘The Black Mozart’ is a disservice to him in that comparing him to Mozart we deny him status as a composer in his own right.

UN: Exactly that, yes. The nickname probably came about as people thinking they were complimenting him, but all that’s meant is that people who know about him don’t really know his music and are just making assumptions about what it actually is. But when you hear it there is a very definite style of his own.

WH: It’s very exciting music, it’s very lively. Perhaps you could mention one or two pieces that we ought to be listening to?

UN: My favourite one at the moment is his ‘Opus. 1’, which is a set of six string quartets. They are extremely virtuosic. Lots of scales and arpeggios and really flashy fireworks. They’re great and really easy to listen to as well. And that’s, I think, where you get a real sense of there being a complete style to him, rather than him sounding ‘a bit like Mozart’.

—

[Music Interlude]

WH: Historian S.I Martin also had a story or two to tell about Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

SM: Anyone familiar with the Chevalier de Saint-Georges?

WH: Yes.

SM: Yes! [Laughs]. Now hehad access to his father’s money. He was given a very correct and proper French education including swordsmanship, in which he excelled; swimming, in which he excelled; music theory, in which he excelled; composition – at which he excelled. He excelled at everything, and you know he wasn’t bad looking either. He ends up becoming a very well-known celebrated composer. Marie-Antoinette, no less, proposed his Directorship of the Paris Conservatory. On grounds of his appearance, that was turned down. Anyway, coming through Greenwich one evening in 1790, he is assailed – so the story goes – by a number of ruffians and, armed only with his violin and bow, he fended them off.

—

[Music interlude]

WH: I was interested to learn more about Luranah and Amanda Aldridge.

UN: Yes, Luranah and Amanda Aldridge were both singers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, born in London. Their father was the African-American Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge. Luranah was quite a well-known opera singer at the time. She actually worked with the Wagners and was due to be in the original cast for ‘The Ring Cycle’ when that was premiered but became ill. Back in London, her sister Amanda taught at Royal College of Music. She looked after her, and it’s thought that her career would’ve progressed more had she not had to look after her sister.

WH: There was a phrase I came across with regard to the two sisters about their ‘breaking the colour barrier’ in the operatic sphere.

UN: It’s quite interesting – you see ‘breaking the colour barrier’ quite a lot for a lot of these musicians, but having looked through it, it seems much more about class. So if you have the right connections, then this ‘colour barrier’ has historically been ignored to a certain point. The assumption there with the ‘colour barrier’ is that they would break this ‘colour barrier’ and then suddenly you’d have lots of musicians from a similar background as them and that wasn’t quite the case. So I’m not sure if I would agree with that in that context.

WH: What does Black History Month mean to you?

UN: Black History Month tends to be when people become more interested in this kind of research. I’d say I don’t really have a personal affinity with the month, because obviously I’m black all the time.

WH: What can musicians at Trinity Laban, and the wider community do to honour the unsung heroes you’ve mentioned and others?

UN: They might not all be heroes to be fair [laughs]. The main area of my research is looking at curation methods and how they can be used to enact change in what we do. We don’t look enough at what’s outside of the canon. So there is music by composers from all over the world that we’re just not looking for, so we don’t know it’s there. The biggest thing, really, is that people need to be more curious when they’re looking at programming concerts, and take more risks.

WH: Excellent. Uchenna Ngwe, it’s been absolutely fascinating to talk to you. Thank you very much.

UN: Thank you, it’s be been great to meet you.

[Music interlude]

WH: I wanted to squeeze in a quick hidden gem listening recommendation of my own. Besides studying at Trinity College of Music in the 1950s, Nigerian musician Fela Kuti lived a fascinating life opposing Nigeria’s militaristic government. I cannot recommend enough that you listen to his track ‘Opposite People’, recorded with the Africa ‘70 band. It’s perfectly paced, catchy and utterly danceable with electrify rhythms, provocative lyrics, tornado sax solos and a horn section theme that will blow your head off. ‘Opposite People’, by Fela Kuti and Africa ’70 – it’s on YouTube. Treat yourself.

—

Back to the walk

WH: We continue to walk deeper into the park…

SM: After a number of ridiculous adventures, Equiano ends up returning to London. He’s still as we would say a teenager, and he is living here in Greenwich up at number 111 Maze Hill. He’s staying there with the Guerin sisters, who were distantly related to – of all people – the gentleman who had sold him down the river! But the Guerin sisters, they’re decent, Christian ladies and they allow him to move freely.

One afternoon when Equiano, as he says, was, ”walking through Greenwich park”, who does he bump into but his old master. Captain Lucas expresses shock, asks him how did he get here, and Equiano says, “by boat” [laugher]. And Captain Lucas retorts, “well I didn’t think you’d walked”. Equiano then berates Captain Lucas for what he believes are monies owed to him. Because, remember, Equiano believes that he was free. So he says to Captain Lucas, “I intend to get my money anyway I can”. Captain Lucas just says “well if you want to, you can try”. But Equiano says this, “I will find a lawyer who will push my case for me”. Now what I think I extraordinary is that he’s what, fifteen, sixteen when he’s saying this to this Royal Naval Captain here in Greenwich park? He had the confidence to present himself in that way. Ultimately, he won’t’ manage to get his money, but it’s a testament to his character.

WH: I’ve walked across the park to Maze Hill to find number 111 where the much-storied Equiano himself lived. It’s a very beautiful building, but as I look further I notice that the top three windows actually have bars across them. There’s no clue to who use to live here, there’s no plaque commemorating his life. And as I look at the building I reflect upon how much of our history is unknown to us. And I think about the building only a few doors up – Vanbrugh Castle – with a plaque proudly commemorating its architect and inhabitant [John Vanbrugh] and I wonder what kind of history of Greenwich future generations will learn about. What kind of knowledge will we have retained?

—

[Music interlude]

WH: There were a few last questions I wanted to ask S. I Martin…

WH: I noticed that during the talk you didn’t really use the term ‘slave trade’ you referred instead to ‘the trade in human lives’. I wondered if you could speak a bit about why you’ve chosen to use those words?

SM: Yes, the use of the words ‘slave trade’ or even the mention of the word ‘slave’ will almost certainly alienate a body of any audience because of its associations with people who are not white. Also, the whole notion of slavery and the condition of slavery is really beyond most twenty-first century imaginations. So I talk specifically about the trade in human lives so that it just makes it more meaningful. It allows people to access the horror and the enormities of those practices

WH: The theme of this month’s podcast is Black History Month. What does Black History Month mean to you?

SM: I think Black History Month is a necessary, but hopefully a temporary, evil in as much as it’s necessary to flag up all sorts of black histories which have otherwise a supernaturally low profile. But particularly if we can charge our programmes with local histories, which again just gives them a great proximity and immediacy rather than reiterating aspects of African-American histories as if they’re universal, then I think Black History Month can serve a good purpose.

—

[Skype sound]

WH: Aaron Chaplin, we’ve just got time for one last question. Could you please give us a hidden gem listening recommendation? This is a piece of music that you love that most people have never come across.

AC: Yeah it’s a song a girl group called Brownstone. They were popular in the nineties actually, and it came on the radio the other day and it sparked joy. I’ve listened to it pretty much every day since. It’s called ‘If you love me’. There’s a warmth in that kind of American R&B that you don’t find in music anymore. It sounds like they’re telling a story. It’s got choral elements, kind of gospel-y. Yeah I just think it’s really beautiful that all those elements combine and make a really great four-minute song.

WH: Excellent. I’m going to get on to YouTube and listen to it as soon as we finish talking.

Well Aaron, thank you very much for taking the time out of your day to talk to us. It’s been a really fascinating interview.

AC: No problem, thank you for having me.

End of call.

—

WH: Trinity Laban Crosscurrent is created by Will Howarth for Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance.

Join us again in December when we’ll be in conversation with influential female figures in the performing arts.