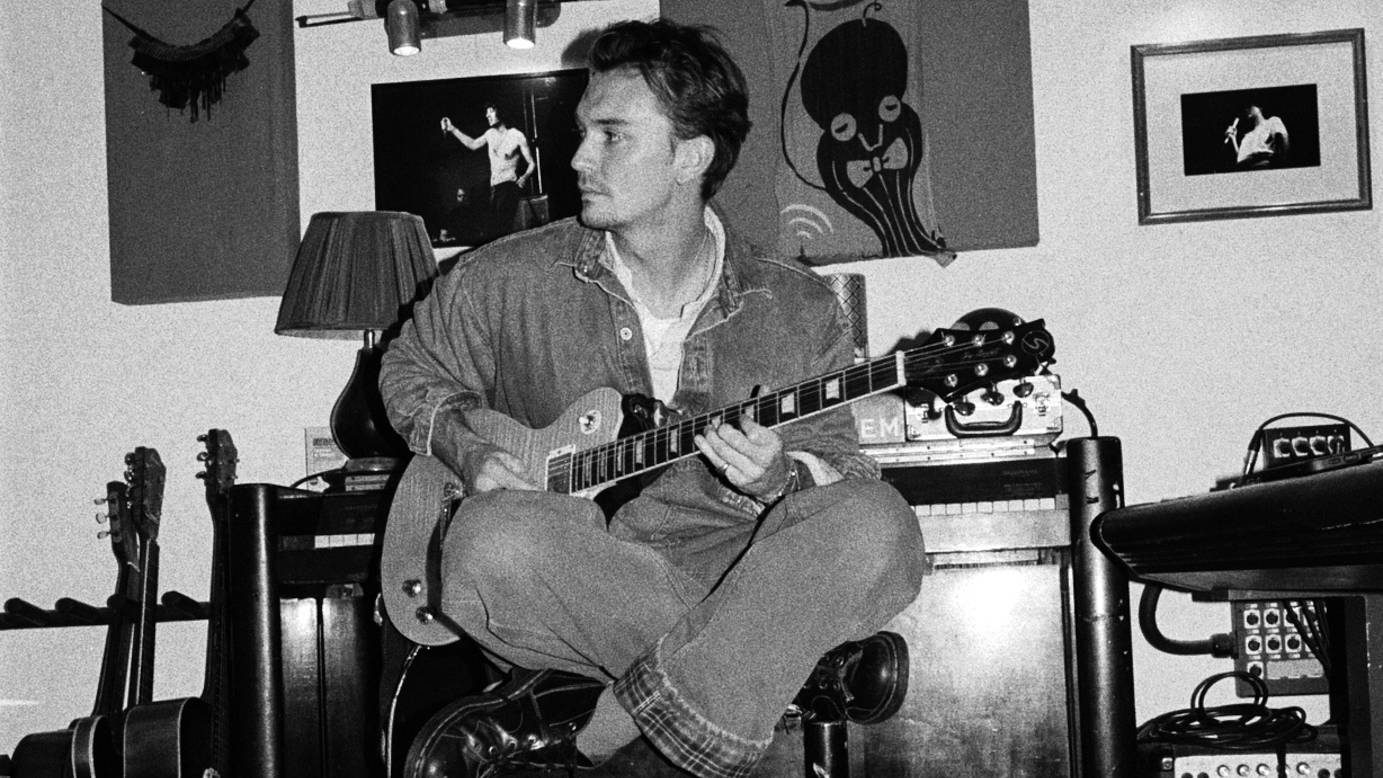

Theo Elwell explores the sound of storytelling and scoring for the screen

When Theo Elwell was a student at Trinity Laban, he received a message from a friend who had just made a short film, asking if he could compose the soundtrack. At first, Theo didn’t know where to start. But as he went to his violin to practise his scales, he found himself experimenting with ideas for the film instead. Before Theo knew it, the sun had gone down and he was completely lost in the process – hours had passed and he had hardly noticed. Theo describes it as a “eureka” moment: a discovery that drove his decision to become a film composer.

Having grown up in a creative family where art was strongly encouraged, Theo started playing the violin when he was five years old. He became a chorister – singing at the Old Royal Naval College Chapel Choir – and toured internationally from a young age, before going on to study the BMus in Music Performance at Trinity Laban on a double scholarship. In 2024, he was awarded a place to study orchestral conducting under Mark Shapiro as part of the extension programme at the Juilliard School of Music. Highlights of his compositional career include international campaigns for Nike and Volvo, BBC’s critically acclaimed series The Holy Land & Us, and recently winning Rising Star at the 2025 Music+Sound Awards. He has orchestrated and composed for a wide range of projects, with one of his most recent scores being in collaboration with Oscar-winner Hoyte van Hoytema (Interstellar, Dunkirk, Oppenheimer), and regularly contributes to the teams of acclaimed composers including Nainita Desai, David Schweitzer, and Dominik Scherrer. In addition to his work for screen, Theo also works as a string arranger and orchestrator for top artists and producers. We spoke to Theo about the behind-the-scenes of composing for the screen and his time at Trinity Laban.

You orchestrated for the Ivor Novello-nominated score for TV Series Three Little Birds, recorded at RAK and Abbey Road’s Angel Studios. What was this experience like?

Abbey Road and RAK studios have always been on my bucket list just to be in. I remember trying to be a runner and coffee boy there when I was 19 and not getting the job so being there in a professional capacity was a total pinch-me moment, and I worked with some of the best musicians I’ve ever heard. The composer, Ben Kwasi Burrell, is amazing and he also studied at Trinity Laban on the jazz course, I believe. It was a brilliant experience and my first time having a major role in that big studio environment, so it was equally terrifying and exciting, but a complete honour.

It was completely different to my previous experiences – the compositions I’d done for TV before were written, sent off to be mixed, and put straight on the TV. The process is very streamlined. In places like RAK and Abbey Road Studios, there are a lot more steps involved: fixers get players in, engineers do their amazing work. It’s a lot more exciting and you feel like you’re more part of the process. To have the luxury of recording live musicians and being with creatives was amazing because I was a performer first and my great love is making music with other people. I studied the violin at Trinity Laban – I grew up playing in the National Children’s Orchestra and National Youth Chamber Orchestra, and I was also a chorister at the Old Royal Naval College Chapel. Those are some of my best musical experiences: meeting other people, singing and playing incredible music. They’ve informed my practice in composition and I play a lot of the instruments I score myself – 95% of the time it’s me playing on the instruments unless I need a really distinct skillset. I desperately miss making music with other people, which is why I was so glad to have these recording sessions – I’d really missed getting people’s heads together and making something that was human and sort of the antithesis of AI-generated music. The session players were some of Ben’s bandmates (he’s a West End Musical Director, as well as a fantastic composer). He got on the podium and said 1, 2, 3, go – and they vamped in sections for ages and improvised. It was amazing to watch.

What is your favourite piece that you’ve written?

I composed the music for an episodic series called The Holy Land and Us that came out three months before the war in Palestine broke out. It was hugely educational because I knew little about the history there previously. It was also my first job outside of full-time work as a runner in a production house. I got this gig and it was a golden ticket, a springboard that allowed me to dive head-first into the creative process. I worked really closely with the director, David Vincent, and we had lots of similar, niche musical interests. The score was a mixture of live strings, electronics, tape machine textures – many of my musical influences all piled into one thing. The show did really well and I’ve more or less built my career so far off the back of people enjoying what I’d done on that. It was a real dream to compose that music, despite it being a harrowing subject matter.

You’re currently the composer for the double BAFTA-winning series Who Do You Think You Are? How did you go about writing the music? What does your creative process look like for composition more generally?

I’ve been scoring the music for Who Do You Think You Are since 2023 and the composer before me, Mike MacLennan, also went to Trinity Laban. It’s really interesting because I have to fit into the musical fabric of the show in a way, but when I joined, the executive producer made it clear that she wanted to push it into a more “modern” realm. She was the executive on The Holy Land show and due to my previous use of electronics in a score, she specified that she was looking for this sound. It works well – the music has got one foot in the classical world but has modern classical scoring. Each episode is different, which is great – we have a different director, different editor, and I get to work with loads of different people. They’ve all got completely varied ideas which makes things interesting.

My creative process varies from project to project. Every time I get a new project in, I have a moment of panic because I forget that I can write music and I’m convinced I can’t do it. From what I’ve seen, this is quite common in the composer community – in fact, I think I’ve read the great Hans Zimmer say a similar thing. It’s like making the first chip out of a massive block of marble. It’s very daunting to begin with, but then you make an inroad somewhere and things start to take shape. I find writing music paralysing, which is probably the reason why I keep wanting to do it. It feeds my curiosity and I’m excited by it. I usually start with a piano sketch, just to map out the harmonic structure, and I’ll go through and watch the cut, mark out the hit points of any particular moments that need attention. Once I’ve built that framework, I’ll start slowly thinking about the instrumentation and orchestration. Before you know it, you’ve got something down. I recently delivered a score for a South American documentary film, which was really exciting. I knew there would be a lot of instruments that could be used organically as well as electronics to make it sound more like my style – I used a lot of charangos and classical nylon string guitars. I always want to make sure I have the sound palette of the film before I start writing. It’s important to have musical cohesion throughout a score, so if you establish a sound palette, you use that more or less consistently throughout, unless there’s a specific stylistic choice that the director wants. I’ll have my instrumentation set out and then dive in with that harmonic sketch that I’ve done at the beginning. I studied the violin at Trinity Laban – it’s such a perfectionist instrument, so I had to unpick certain practices. Lots of instruments that I integrated into this documentary were a little out of tune – I did that on purpose. I think it adds a humanity to the music. It was a really interesting journey from being a professional-ready violinist to being an artist in a different way.

Do you have a stand-out performance from your time at Trinity Laban?

I loved my violin teachers at Trinity Laban, I’m still in touch with some of them. I remember my second-year recital quite clearly. I really wanted to do the first movement from Sibelius’s Violin Concerto. It’s so unbelievably hard, but I did do it and it went quite well. I really enjoyed learning it – this process of stretching and challenging yourself is one I got really addicted to. I think lots of people do at conservatoire. CoLab performances felt like a turning point for me. We did an installation where everyone recorded their parts of Spem in alium by Thomas Tallis and we put lots of speakers in a room. The public walked through and you could hear different voices coming out. That was really interesting for me.

I did the modules “Digital Musicianship” and “Scoring for Media” with the brilliant Guy Harries, who I owe a lot to. We had to write and compose electronic music and perform it in one, and score a scene from a film in the other. As a Jon Hopkins, Four Tet, and Burial fan, that was a dreamy moment for me to pause my classical violin studies for a second and explore a new avenue, and Guy was very supportive as I was beginning to explore the world of film scoring.

What advice do you have for prospective students looking to study composition? And can you tell about some of your upcoming and current projects?

Do as many things as you can and work hard. If you’re interested in going to seminars from different subjects, ask and do it. I remember asking the late great John Ashton-Thomas to come along to composition and orchestration classes. It wasn’t really the done thing, but I wanted to go and I think Trinity Laban really values collaborating – mixing across the artforms. The teaching is entrepreneurial and innovative. If you find something remotely interesting, then go to the gig, make friends across the board, and make music together. Life gets pretty intense after you finish studying and you don’t have much opportunity for those kinds of moments any more.

I’m doing a lot of string arranging which is my first love – that’s basically why I carried on playing the violin and why I’m in this career. It’s a dream to be able to get paid to do that and to work with these amazing artists all over the world. Lots of EPs for different artists will be coming out this year and next year – I did some work for Tom Misch for a song on his latest EP. He’s a musician who was also at Trinity Laban. A lot of my work is within composing teams, which is great, I love doing that. I’m carrying on with Who Do You Think You Are with a fourth season next year, and I’ve just signed onto a new series for BBC Studios, as well as a couple of projects in LA and New York with some new directors.